Van Gogh was a compulsive and eloquent correspondent. The majority of his letters were written to his brother Theo, an art-dealer who supported Vincent throughout his difficult artistic career. Vincent also wrote to other family members, including his sister Wilhelmina. Other artists, notably Anton van Rappard, Emile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, were also, at different phases of Vincent’s life, recipients of his letters. The originality of his ideas about art, nature and literature, combined with his deep understanding of these subjects, make Van Gogh’s letters much more than a personal expression of feelings: they attain the status of great literature. In reading the letters one encounters not only a sensitive, determined and exceptionally hard-working man, but also someone possessed of a powerful intellect; this exhibition challenges the view that Van Gogh was an erratic genius by allowing the viewer a rare insight into his artistic process through the intimate medium of his correspondence. Together the letters create a “self-portrait,” and reveal the ways in which Van Gogh defined himself as an artist and as a human being.

The focus of the exhibition is the artist’s remarkable correspondence. Over 35 original letters, rarely exhibited to the public due to their fragility, are on display in the main galleries of Burlington House, together with around 65 paintings and 30 drawings that express the principal themes to be found within the correspondence. The exhibition offers a unique opportunity to gain an insight into the complex mind of Vincent van Gogh.

In addition to lending almost all the letters in the exhibition, the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, has made available twelve important paintings. Other major lenders include the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, together with other museums and private collections worldwide.

Born in Zundert in the southern Netherlands in 1853, Van Gogh was the second of six children of a Protestant pastor. In his early adult life, he worked for a firm of art-dealers in The Hague and London, before becoming a missionary worker. His career as an artist began only in 1880, when he was 27. During his ten-year artistic career, which his suicide cut tragically short in 1890, Van Gogh’s output was prodigious: largely self-taught, he produced over 800 paintings and 1,200 drawings.

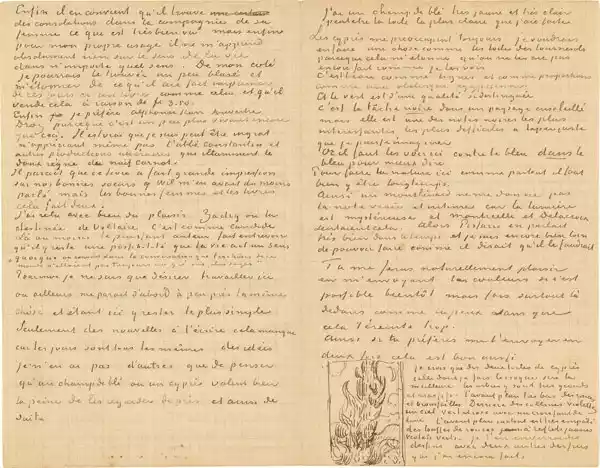

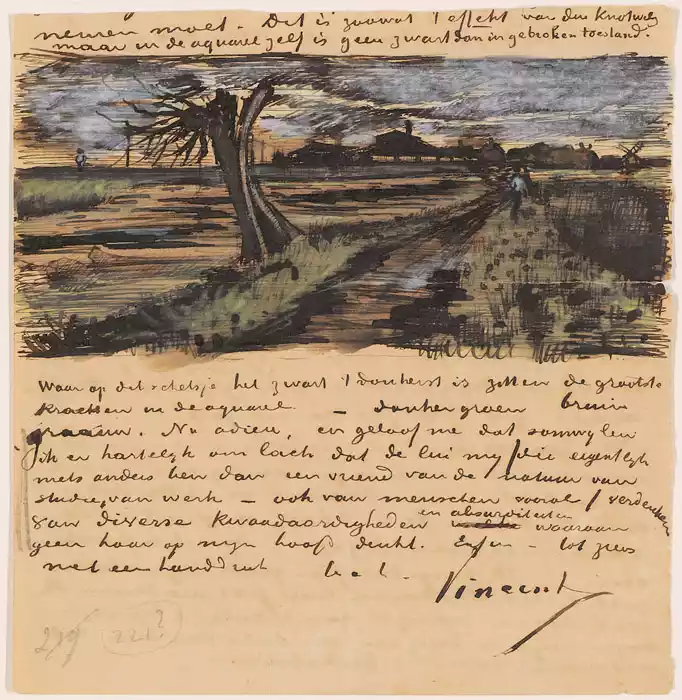

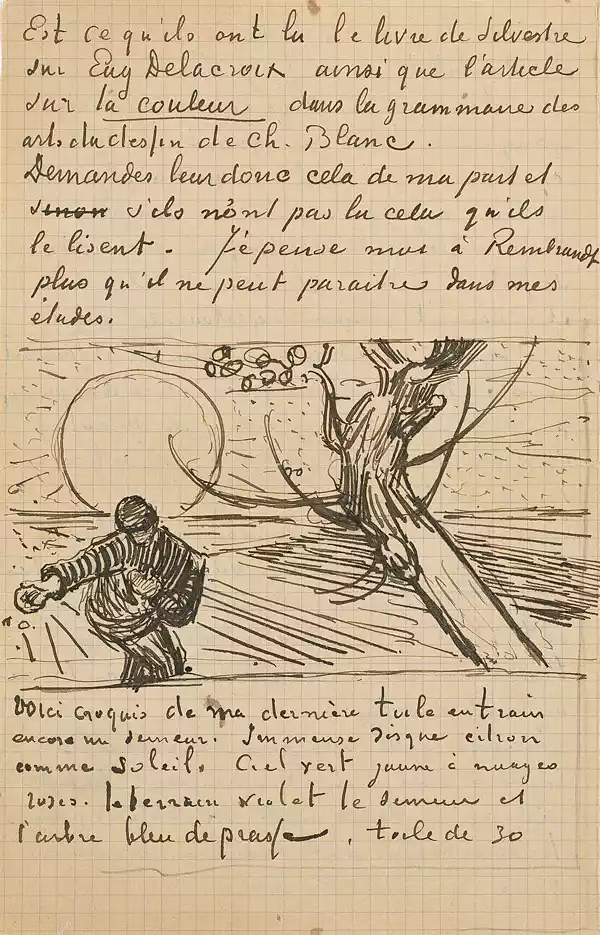

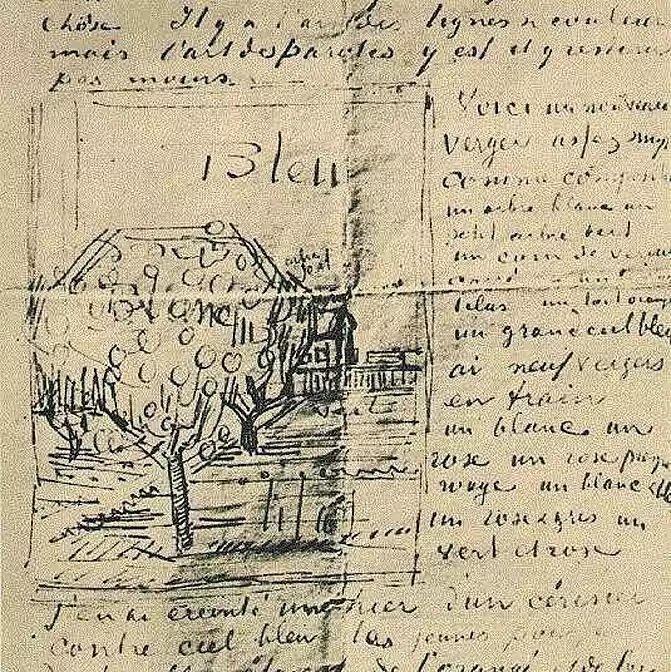

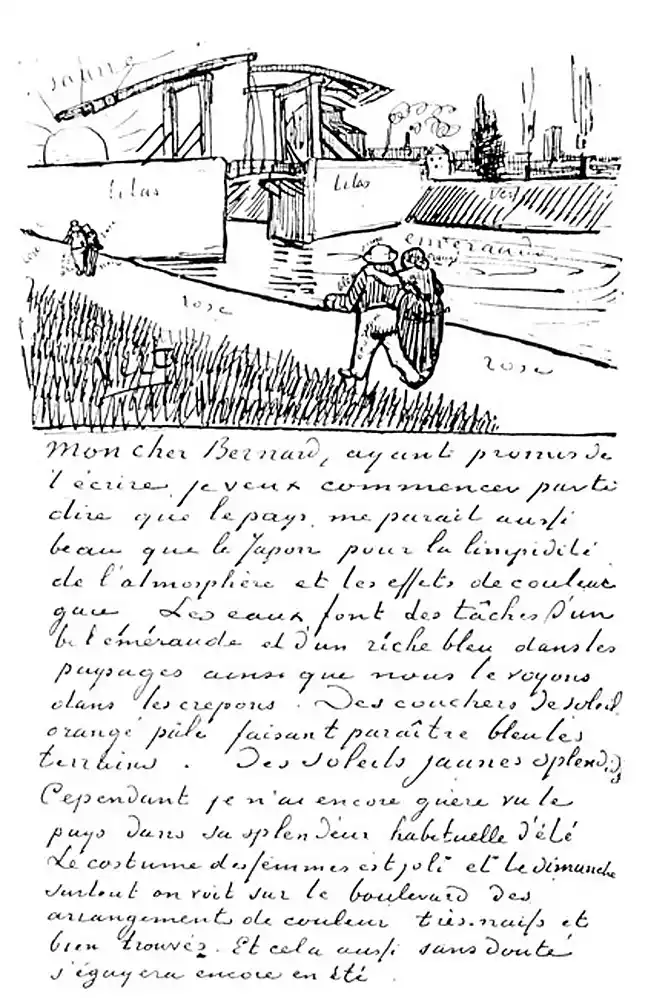

Taking the letters as its starting point, The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters views the paintings and drawings from the perspective of the correspondence. The letter sketches that Van Gogh frequently used to show a work in progress or a completed work are a fascinating part of the correspondence, and many are shown alongside the paintings or drawings on which they are based.

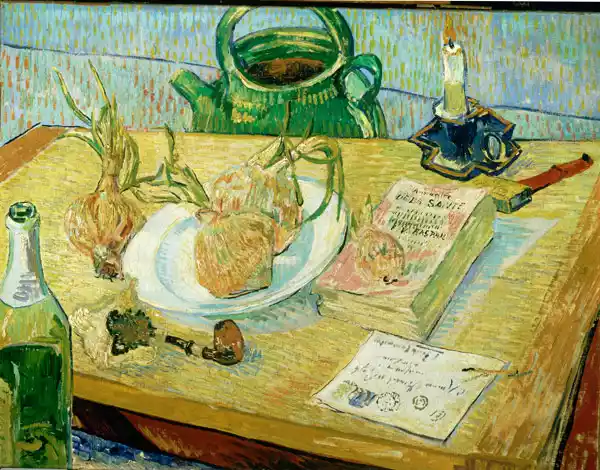

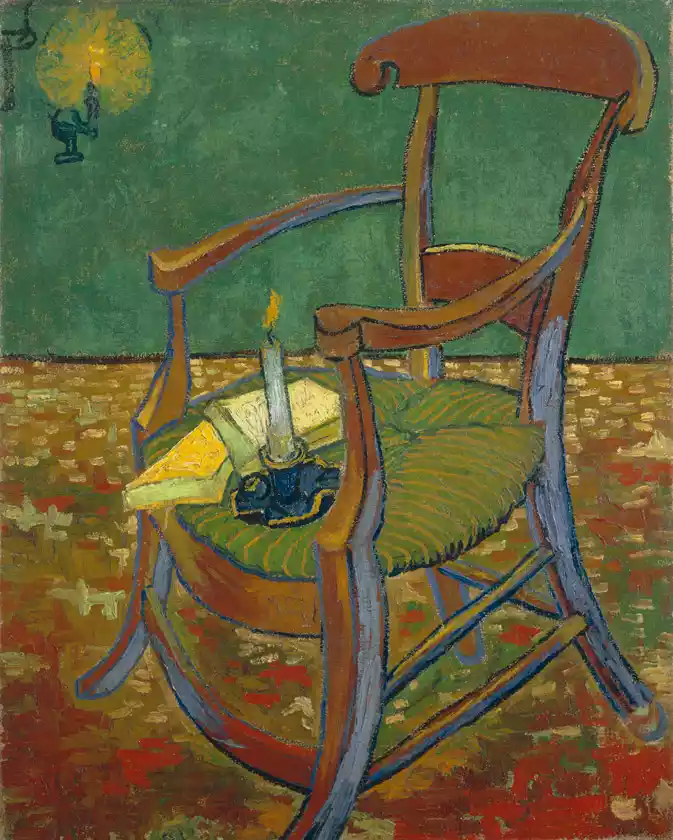

Highlights of the exhibition include Self-portrait as an Artist (1888) and The Yellow House (1888) from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Still-life: Drawing Board with Onions (1889) from the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo; Vincent’s Chair with His Pipe (1888) from the National Gallery, London; and Entrance to the Public Park in Arles (1888) from the Phillips Collection, Washington DC.

Examining such themes as the role of color in painting, the cycles of nature, friendship, religion, and literature, the exhibition celebrates the new edition of the artist’s correspondence Vincent van Gogh —The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, published by Thames & Hudson in October 2009. The result of 15 years of scholarship by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker of the Van Gogh Museum, the complete correspondence of Vincent van Gogh is published as a printed edition in three languages and as an integral web edition, thereby providing the worldwide public with a wealth of new information. The exhibition is based on many insights that the new and extensive research into the letters has produced.

The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and His Letters is curated by Ann Dumas of the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in collaboration with Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Vincent van Gogh’s and Emile Bernard’s Friendship as Shown in Letters

Twenty letters from Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890) to the artist and poet Émile Bernard (French, 1868-1941) are the subject of an unprecedented exhibition on view only at The Morgan Library & Museum from September 28, 2007, through January 6, 2008. Painted with Words: Vincent van Gogh’s Letters to Émile Bernard offers a rare look at the life and creative process of the legendary master of modern art through the letters van Gogh wrote to his friend and colleague Bernard as well as twenty-two paintings, drawings and watercolors that the two artists discussed or exchanged. Comprised of missives and artwork from the peak of van Gogh’s creativity, while he was living in the south of France (1888–1889), the exhibition explores in depth for the first time the important role correspondence played in how van Gogh thought about his work and communicated his progress to his contemporaries.

Unseen by scholars and the public for nearly seventy years and never before exhibited, this cache of letters to Bernard is unlike any of van Gogh’s other known writings. Distinguished by their frank, vibrant, and often humorous tone, the letters reveal everything from van Gogh’s artistic methods to his emotional struggles to his sharp observations about daily life. Six include sketches that complement written descriptions of artworks and are presented alongside related works by van Gogh and Bernard, most of which have not recently been “We are deeply grateful to Gene and Clare Thaw for their exceptional gift to the Morgan of the van Gogh letters. They enrich our holdings of artists’ letters tremendously by adding significant correspondence by a figure essential to the development of modern art.”

Painted with Words is organized by Jennifer Tonkovich, Curator, Drawings and Prints, The Morgan Library & Museum.

After meeting in Paris in 1886, Vincent van Gogh and fellow student Émile Bernard embarked on a close friendship and in 1887 began a two-year correspondence that spanned the final years of van Gogh’s brilliant, psychologically troubled life prior to his suicide in 1890. Van Gogh’s letters to Bernard illuminate the many ways in which the artists inspired and encouraged one another. The Dutch artist took the role of older, wiser brother to Bernard, praising or criticizing his paintings, drawings, and poems. Bernard became a friend and confidant to van Gogh, living alone in Arles. The letters also chronicle van Gogh’s struggles, as he often solicited Bernard’s advice or opinion on artistic issues. While the whereabouts of Bernard’s letters to van Gogh remains a mystery, his admiration for van Gogh is well documented — Bernard became an early promoter of van Gogh’s genius, working to establish his status as a major artist in the years leading to and following his death.

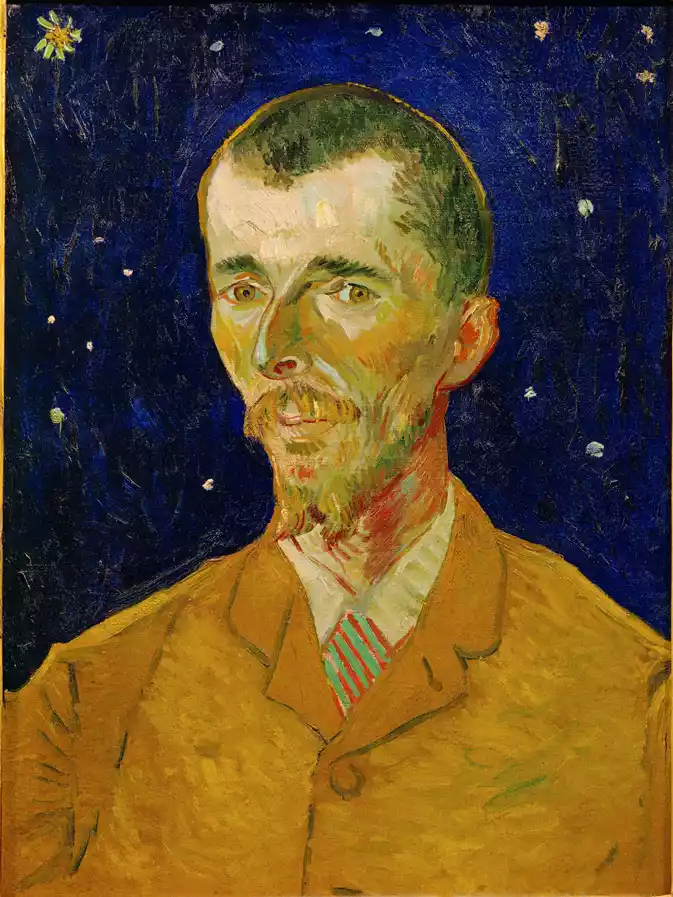

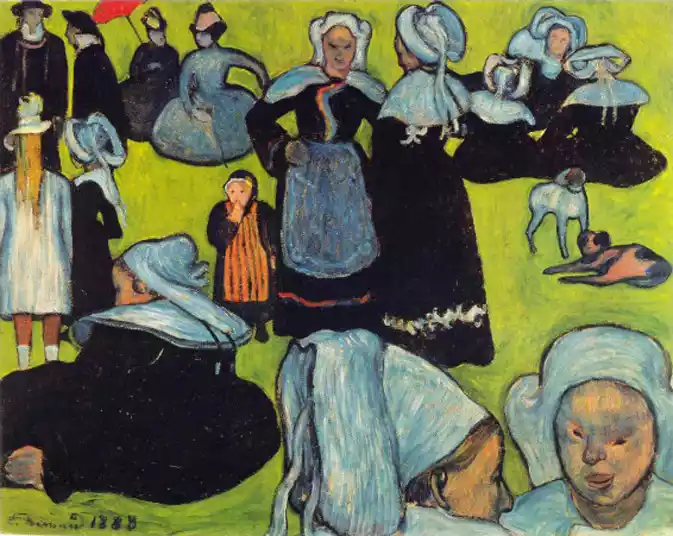

Rebelling against his father’s wishes, Bernard chose to become an artist when he was sixteen years old. Two years later he met van Gogh in Paris and began a friendship significant for both artists. Bernard had a lengthy career, but his best work is confined to the late 1880s, when he worked in Paris and Brittany. In Brittany, along with Gauguin, Bernard developed the cloissonist style, with Its heavy contours and flat areas of color. Bernard’s work as an art critic and catalyst was equally important. He published the letters van Gogh sent to him shortly after the artist’s death and organized one of the first French retrospectives of van Gogh’s work in 1892. In addition he corresponded with Gauguin, Cézanne, Odilon Redon among others, and was the author of several important articles on contemporary art.

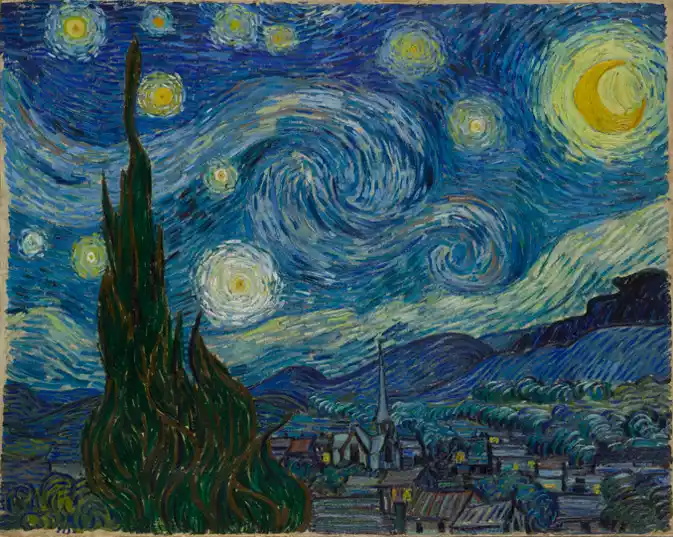

Painted with Words is the first exhibition to address the pivotal role Bernard’s friendship played while the Dutch artist was living in Arles. Writing to a fellow artist, van Gogh freely conveyed his thoughts about life and art in an open and expressive manner, providing incomparable insight into his mind and talent. The letters touch on a broad range of topics — from the philosophical to the mundane, from the amusing to the explicit. In a letter from Arles dated June 19, 1888, van Gogh wrote, “I am in better health here than in the north — I even work in the wheat fields at midday, in the full heat of the sun, without any shade whatever, and there you are, I revel in it like a cicada.” In the same letter, he went on to describe a vision of what would later become one of his most iconic subjects, Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), now in the collection of Musée d’Orsay, Paris:

”But when will I do the starry sky, then, that painting that’s always on my mind? Alas, alas, it’s just as our excellent pal Cyprien says, in “En ménage” by J. K. Huysmans: “the most beautiful paintings are those one dreams of while smoking a pipe in one’s bed, but which one doesn’t make. But it’s a matter of attacking them nevertheless, however incompetent one may feel vis-à-vis the ineffable perfections of nature’s glorious splendors.“

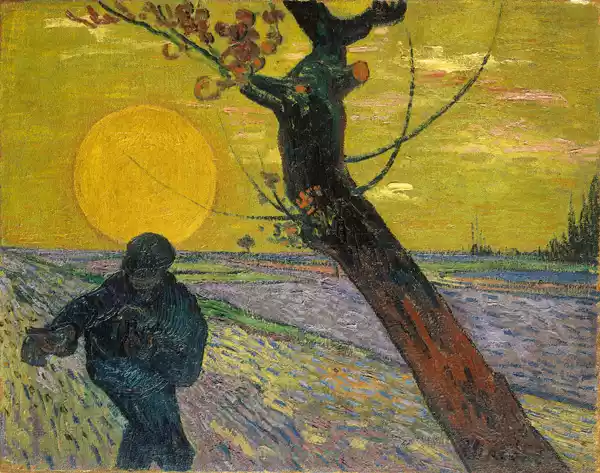

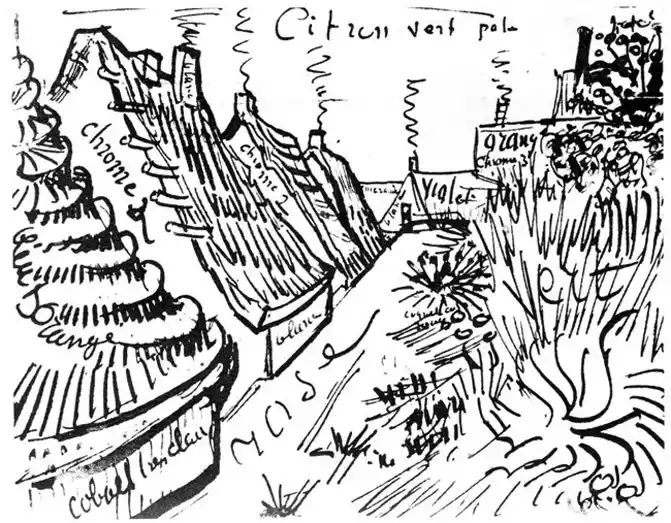

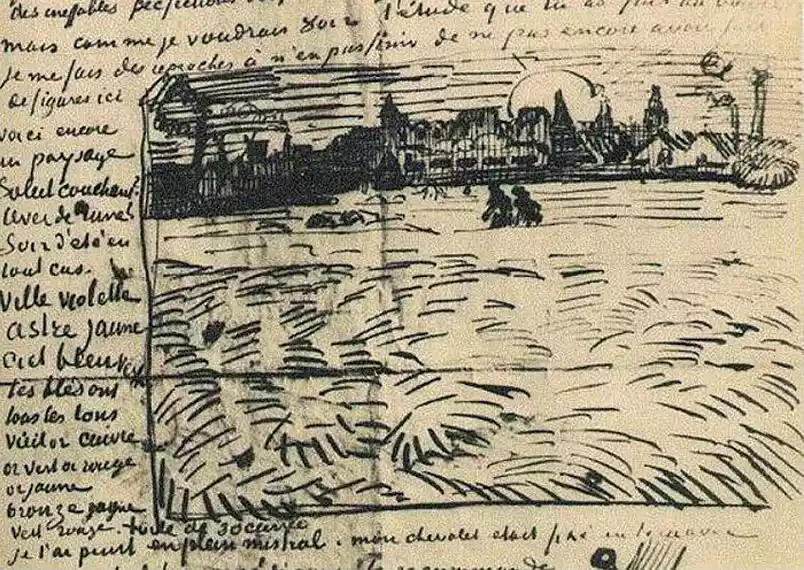

Both artists’ letters included sketches to provide an idea of work in progress. Van Gogh’s contained studies related to The Sower (1888), The Langlois Bridge (1888), Cottages at Saintes-Maries (1888), Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries (1888), and View of Arles at Sunset (1888). In a letter written just as he had begun work on View of Arles at Sunset, van Gogh wrote, “Here’s another landscape.

“Setting sun? Moonrise? Summer evening, at any rate. Town violet, star yellow, sky blue-green; the wheat fields have all the tones: old gold, copper, green gold, red gold, yellow gold, green, red, and yellow bronze. Square no. 30 canvas.” Along with the letter, the exhibition includes the sketch and the full-scale répétition, or drawing replicating a painted composition, that van Gogh sent to Bernard after finishing the painting. Such répétitions allowed van Gogh to experiment with translating painted works into graphic form. They are among the artist’s most accomplished works on paper.

Van Gogh’s pivotal trip to the Mediterranean village of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer — engendering a stylistic turning point in — is documented by a long letter with sketches of resulting compositions. One, a study of cottages at Saintes-Maries, is explored through the letter sketch and three related drawings of the subject that reveal the artist’s working method. Likewise, van Gogh’s drawing after the portrait of a young girl known as La Mousmé (1888), with its lengthy color notations, attests to the ways in which van Gogh communicated new developments in his work to his younger colleague.

Several works chronicle the artists’ mutual interests, including Bernard’s portrait of his grandmother, which van Gogh praised highly and which served as inspiration for his own portrait of an aged woman in Arles. Van Gogh often wrote about the critical importance of portraiture to modern painting, and such portraits constituted a significant portion of his output while in Arles. His desire to communicate his progress in this genre is demonstrated by his painting of a Zouave officer and the related watercolor he inscribed and sent to Bernard.

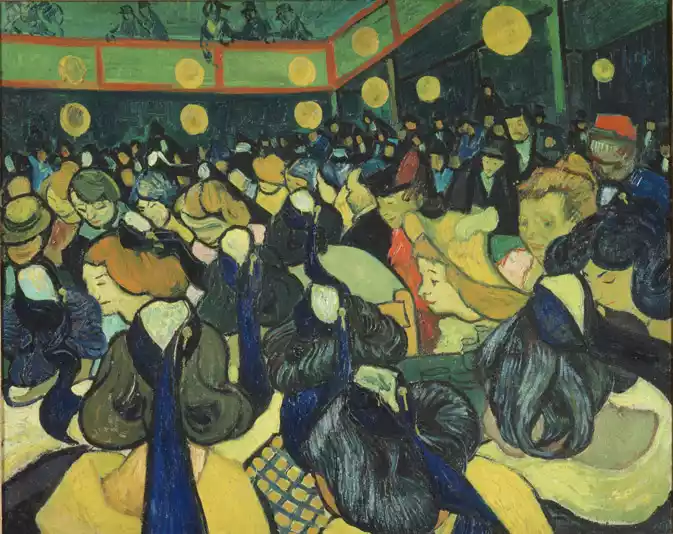

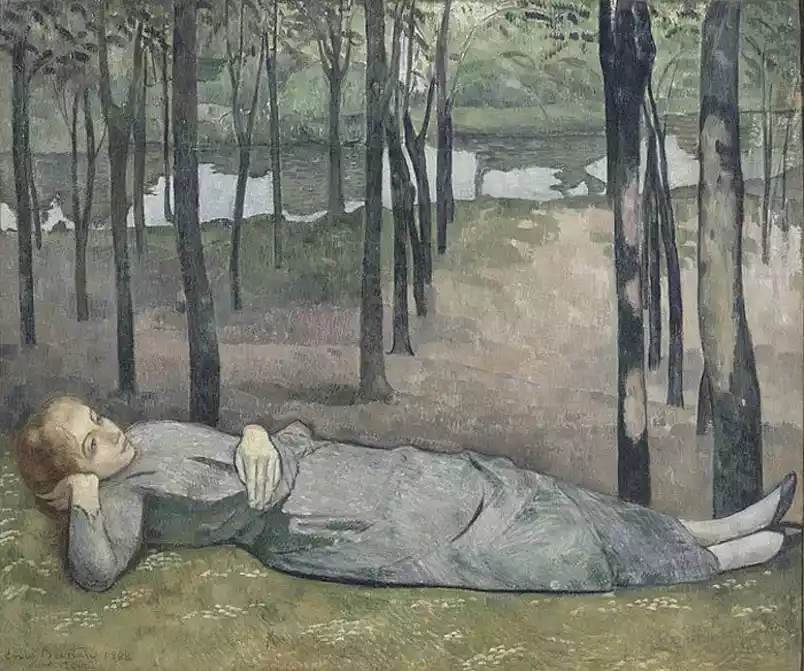

Van Gogh was also interested in Bernard’s work in Pont-Aven, Brittany, where, together with the artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Bernard developed the cloissonist style, characterized by heavy contours and flat areas of color. Gauguin brought Bernard’s painting Breton Women in a Meadow (1888) to Arles, where van Gogh copied the work in his watercolor Breton Women in the Plain of Pont-Aven (1888). Both works are on view in the exhibition alongside a letter from van Gogh to Bernard sent from Saint-Rémy in October 1889, in which van Gogh praised Bernard’s work at Pont-Aven, saying “Well, I’ll be very curious to see studies of Pont-Aven. But for yourself, give me something fairly worked up. It will work out, anyway, because I like your talent so much that I’d be very pleased to make a small collection of your works, bit by bit.”

Although his career as an artist lasted only ten years, van Gogh produced more than 860 paintings and about 1,200 watercolors and drawings. He also wrote more than 800 letters, the majority to his brother Theo. Both his works and his letters contributed to his legacy as a psychologically tortured, struggling artist who ranks among the most important and influential modern painters.

Van Gogh produced some of his most celebrated works during the last two and a half years of his life, while in the south of France, first at Arles (February 1888-April 1889), then Saint-Rémy (May 1889-May 1890), and finally Auvers (June-July 1890). The letters, drawings, and paintings from this period document his artistic maturity and the application of his ideas about painting.

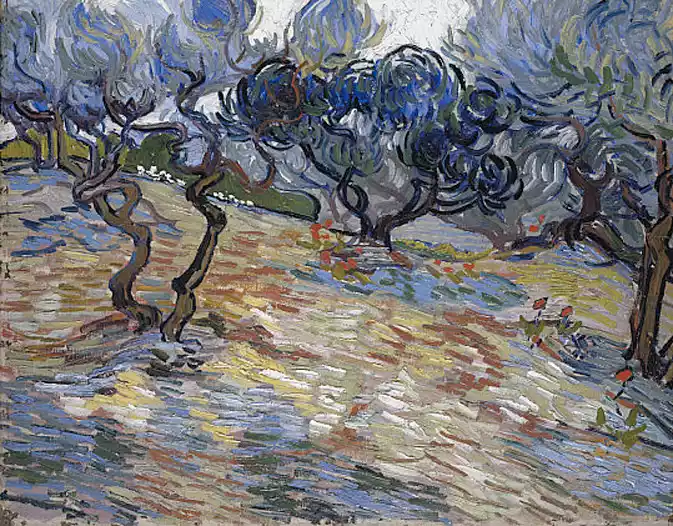

Major paintings discussed in the letters, such as Enclosed Field (1889) and Olive Trees (1889), provide context for van Gogh’s correspondence and represent the works chronicled in his writings to Bernard. Van Gogh felt strongly that his paintings of olive trees contained as much religious feeling as Bernard’s figurative depictions of Christ on the Mount of Olives.

As the organizer of one of the first retrospectives of van Gogh’s work in Paris and the author of several early, seminal articles on the artist, Bernard made a significant contribution to van Gogh’s legacy as a ground-breaking artist and an icon in the canon of art history. Bernard had begun trying to establish van Gogh’s reputation before his friend’s death. Recognizing the significance of his letters and their potential interest to a wider public, Bernard showed them to important art critics. Within three years of van Gogh’s death, Bernard published some of the letters and enclosed sketches in the pages of the art and literature periodical Mercure de France. The letters to Bernard remained a distinct group. They were published by Paris dealer Ambroise Vollard in 1911 and translated into English from French by Douglas Cooper in 1938. Painted with Words explores Bernard’s contributions through a selection of periodicals and publications.

Of the 22 known letters van Gogh wrote to Bernard, all but two are on view at the Morgan. Nineteen of the 20 exhibited letters to Bernard have been promised to the Morgan by Eugene and Clare Thaw; the remaining letter is on loan courtesy of the Fondation Custodia in Paris. One of the missing two letters is known only through an old photograph and is considered lost; the other belongs to a private collection. The exhibition also includes an additional letter van Gogh wrote to Paul Gauguin — his and Bernard’s mutual friend. This letter features a sketch related to one of van Gogh’s most acclaimed paintings, Bedroom at Arles (1888), now in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. By the time this letter to Gauguin arrived in Pont-Aven, Gauguin had already left and Bernard probably received it instead. For this reason, this last letter to Gauguin is traditionally included in letters van Gogh wrote Bernard. It was acquired previously by Eugene Thaw and promised to the Morgan in 2000.

Considering the Similar Styles of Van Gogh’s Drawings and Paintings

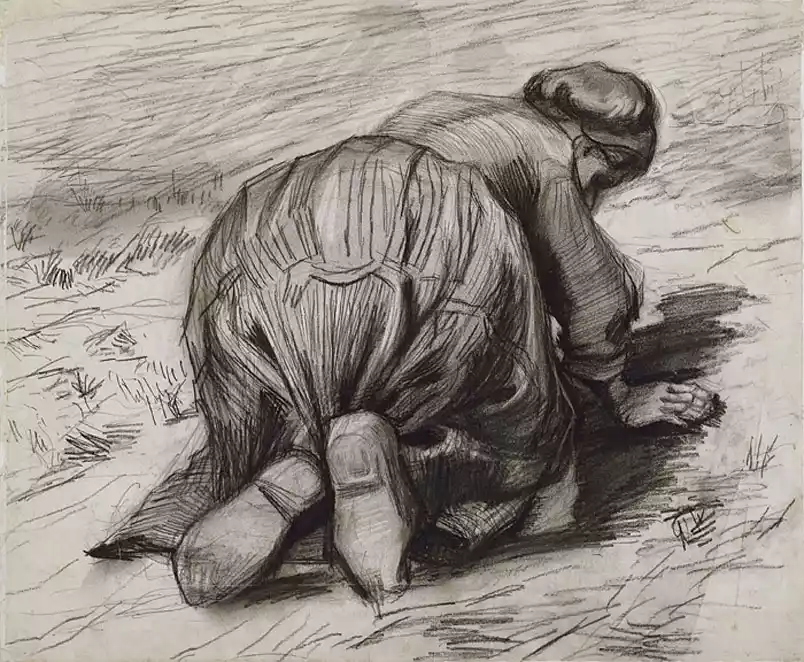

Drawn Pictures is concerned with the two-way relationship between van Gogh’s drawings and his paintings, focusing particularly on the last creative years of his time in Paris and Arles up to his stays in Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise. Shown will be large-format drawings and paintings executed with chalk, watercolours and also thinned oils, whose subjects — portraits, still lifes and landscapes — are portrayed in a manner that has more to do with drawing than with painting.

Despite the different representational capacities of drawing and painting, in the work of van Gogh both media exhibit comparable stylistic structures. This led, on the one hand, to a renunciation of spatial illusion and volume and, on the other, to the artist’s own distinctive expressive style. The calculated and well-practised graphic approach that van Gogh also used in paintings — of quite different subjects — suggests a deliberate working method. Juxtaposition with the drawings should tend to revise the popular view of van Gogh as an artist solely driven by emotional outbursts.

Vincent Willem van Gogh (March 30, 1853-July 29, 1890), a Dutch Post-Impressionist artist made paintings and drawings among the world’s best known, most popular and most expensive.

Van Gogh spent his early years working an art dealer firm. After a brief spell as a teacher, he became a missionary worker in a poor mining region. He did not embark on a career as an artist until 1880. Initially, he worked only with sombre colours, until he found Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism in Paris. He incorporated their brighter colours and painting style into his own recognizable style, that he fully developed during the time he spent at Arles, France. He produced more than 2,000 works, including around 900 paintings and 1,100 drawings and sketches, during the last ten years of his life. Most of his best-known works were produced in the final two years of his life, during which time he cut off part of his left ear following a breakdown in his friendship with Paul Gauguin. After this he suffered recurrent bouts of mental illness, which led to his suicide.

Central to Van Gogh’s life was his brother Theo, who continually and selflessly provided financial support. Their lifelong friendship is documented in many letters from August 1872 onwards. Van Gogh is a pioneer of what came to be known as Expressionism. He had an enormous influence on 20th century art, especially on the Fauves and German Expressionists.

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born in Groot-Zundert, a village close to Breda in the Province of North Brabant in the southern Netherlands. Van Gogh was the son of Anna Cornelia Carbentus and Theodorus van Gogh, who was a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church. He was given the same name as his grandfather — and a first brother stillborn exactly one year before. It has been suggested that being given the same name as his dead elder brother might have had a deep psychological impact on the young artist, and that elements of his art, such as the portrayal of pairs of male figures, can be traced back to this. The practice of reusing a name in this way was not uncommon. The name “Vincent” was often used in the Van Gogh family: the baby’s grandfather was called Vincent van Gogh (1789-1874); he had received his degree of theology at the University of Leiden in 1811. Grandfather Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers, including another Vincent, referred to in Van Gogh’s letters as “Uncle Cent.” Grandfather Vincent had perhaps been named after his own father’s uncle, the successful sculptor Vincent van Gogh (1729-1802). Art and religion were the two occupations to which the Van Gogh family gravitated.

Four years after Van Gogh was born, his brother Theodorus (Theo) was born on May 1, 1857. There was also another brother named Cor and three sisters, Elisabeth, Anna and Wil. As a child, Van Gogh was serious, silent and thoughtful. In 1860 he attended the Zundert village school, where the only teacher was Catholic and there were around 200 pupils. From 1861 he and his sister Anna were taught at home by a governess, until October 1, 1864, when he went away to the elementary boarding school of Jan Provily in Zevenbergen, the Netherlands, about 20 miles (32 km) away. He was distressed to leave his family home, and recalled this even in adulthood. On September 15, 1866, he went to the new middle school, Willem II College in Tilburg, the Netherlands. Constantijn C. Huysmans, who had achieved a certain success himself in Paris, taught Van Gogh to draw at the school and advocated a systematic approach to the subject. In March 1868 Van Gogh abruptly left school and returned home. His comment on his early years was: “My youth was gloomy and cold and sterile …”

In July 1869, at 15, he obtained a position with art dealer Goupil & Cie in The Hague through his Uncle Vincent (“Cent”), who had built up a good business which became a branch of the firm. After training, Goupil transferred him to London in June 1873, where he lodged at 87 Hackford Road, Brixton working at Messrs. Goupil & Co., 17 Southampton Street. It was a happy time for Van Gogh: he was successful at work, and was already, at 20, earning more than his father. He fell in love with his landlady’s daughter, Eugénie Loyer, but when he finally confessed his feeling to her, she rejected him, saying that she was already secretly engaged to a previous lodger. Vincent became increasingly isolated and fervent about religion. His father and uncle sent him to Paris, where he grew resentful at art’s commodification, and he manifested this to customers. On April 1, 1876, it was agreed his employment should end.

His religious emotion grew to where he felt it was his true vocation in life, and he returned to England to do unpaid work, first as a supply teacher in a small boarding school the Ramsgate harbour; he made some sketches of the view. The proprietor of the school relocated to Isleworth, Middlesex. Vincent decided to walk to the new location. This new position did not work out, and Vincent became a nearby Methodist minister’s assistant in wanting to “preach the gospel everywhere.”

He returned home at Christmas tht year, and worked in a bookshop in Dordrecht for six months, but unhappy in this new position, he spent most of his time in the back of the shop either doodling, or translating passages from the Bible into English, French, and German. His roommate from this time, a young teacher called Görlitz, later recalled that Vincent ate frugally, preferring to eat no meat. In an effort to support his wish to become a pastor, his family sent him to Amsterdam in May 1877 where he lived with his uncle Jan van Gogh, a rear admiral in the navy. Vincent prepared for university, studying for the theology entrance exam with his uncle Johannes Stricker, a respected theologian who published the first Life of Jesus in the Netherlands. Vincent failed at his studies and abandoned them. He left uncle Jan’s house in July 1878. He then studied, but failed, a three-month course at the Protestant missionary school (Vlaamsche Opleidingsschool) in Laeken, near Brussels.

In January 1879 Van Gogh got a temporary post as a missionary in the village of Petit Wasmes in the coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium, bringing his father’s profession to people felt to be the most wretched and hopeless in Europe. Taking Christianity to what he saw as its logical conclusion, Vincent opted to live like those he preached to, sharing hardships to the extent of sleeping on straw in a hut at the back of the baker’s house where he was billeted; the baker’s wife used to hear Vincent sobbing all night in the hut. His choice of squalid living conditions did not endear him to appalled church authorities, who dismissed him for “undermining the dignity of the priesthood.” After this he walked to Brussels, returned briefly to the Borinage, to the village of Cuesmes, but acquiesced to pressure from his parents to come “home” to Etten. He stayed there until around March the following year, to the increasing concern and frustration of his parents. There was considerable conflict between Vincent and his father, and his father made enquiries about committing his son to a lunatic asylum at Geel. Vincent fled back to Cuesmes where he lodged with a miner named Charles Decrucq, with whom he stayed until October. He became increasingly interested in everyday people and scenes around him that he recorded in drawings.

In 1880, Vincent followed Theo’s suggestion and took up art in earnest. In autumn 1880, he went to Brussels, intending to follow Theo’s suggestion to study with prominent Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded Van Gogh (despite his aversion to formal schools of art) to attend the Royal Academy of Art. There he not only studied anatomy, but the standard rules of modelling and perspective, all of which, he said, “you have to know just to be able to draw the least thing.” Vincent wished to become an artist while in God’s service as he stated, “to try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another in a picture.”

In April 1881, Van Gogh went to live in the countryside with his parents in Etten and continued drawing, using neighbours as subjects. Through the summer he spent time walking and talking with his recently widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker, daughter of his mother’s older sister and Johannes Stricker, who had shown real warmth towards his nephew. Kee was seven years older than Vincent, and had an eight-year-old son. Vincent proposed marriage, but she refused with the words: “No, never, never” (niet, nooit, nimmer). At the end of November he wrote a strong letter to Uncle Stricker,and then, soon after, hurried to Amsterdam and talked with Stricker again on several occasions,but Kee refused to see him at all. Her parents told him “Your persistence is disgusting”. In desperation he held his left hand in the flame of a lamp, saying, “Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame.” He did not clearly recall what happened next, but assumed his uncle blew out the flame. Her father, “Uncle Stricker,” as Vincent refers to him in letters to Theo, made it clear there was no question of Vincent and Kee marrying, given Vincent’s inability to support himself financially. What he saw as hypocrisy in his uncle and former tutor affected Vincent deeply. At Christmas he quarreled violently with his father, refusing a gift of money, and immediately left for The Hague.

In January 1882 he settled in The Hague, where he called on his cousin-in-law, painter Anton Mauve, who encouraged him to paint. He soon fell out with Mauve, perhaps over the issue of drawing from plaster casts; Mauve appeared suddenly to go cold towards Vincent, not returning a couple of his letters. Vincent guessed that Mauve had learned of his new domestic relationship with the alcoholic prostitute, Clasina Maria Hoornik (born February 1850, The Hague; she was known as Sien) and her young daughter. Van Gogh had met Sien near the end of January. Sien had a five year-old daughter, and was pregnant. She had already had two other children who had died, although Vincent was unaware of this. On July 2, Sien gave birth to a baby boy, Willem. When Vincent’s father discovered the details of this relationship, pressure was put on Vincent to abandon Sien and her children. Vincent was at first defiant in the face of his family’s opposition.

His uncle Cornelis, an art dealer, commissioned 20 ink drawings of the city from him; they were completed by the end of May. In June Vincent spent three weeks in a hospital suffering gonorrhoea. In the summer, he began to paint in oil. In autumn 1883, after a year with Sien, he abandoned her and the two children. Vincent had wanted to move the family from the city, but in the end only he made the break.

It is possible that lack of money had pushed Sien back to prostitution; the home had become a less happy one, and Vincent may have felt family life was irreconcilable with his artistic development. When Vincent left, Sien gave her daughter to her mother, and baby Willem to her brother, and moved to Delft and then Antwerp. Willem remembered being taken to visit his mother in Rotterdam at around the age of 12, where his uncle tried to persuade Sien to marry in order to legitimize the child. Willem remembered his mother saying: “But I know who the father is. He was an artist I lived with nearly 20 years ago in The Hague. His name was Van Gogh.” She then turned to Willem and said “You are called after him.” Willem believed himself to be Van Gogh’s son, but the timing of the birth makes this unlikely. In 1904 Sien drowned herself in the river Scheldt

Van Gogh moved to the Dutch province of Drenthe in the north of the Netherlands, and in December, driven by loneliness, to stay with his parents who were by then living in Nuenen, North Brabant, also in the Netherlands.

In Nuenen, he devoted himself to drawing — paying boys to bring him birds’ nests — and rapidly sketching the weavers in their cottages. In autumn 1884, a neighbour’s daughter, Margot Begemann, ten years older than Vincent, accompanied him constantly on his painting forays and fell in love, which he reciprocated (though less enthusiastically). They agreed to marry, but were opposed by both families. Margot tried to kill herself with strychnine and Vincent rushed her to the hospital.

On March 26, 1885, Van Gogh’s father died of a stroke. Van Gogh grieved deeply. For the first time there was interest from Paris in some of his work. In spring he painted what is now considered his first major work, The Potato Eaters (Dutch De Aardappeleters). In August his work was exhibited for the first time, in the windows of a paint dealer, Leurs, in The Hague. In September he was accused of making one of his young peasant sitters pregnant, and the Catholic village priest forbade villagers from modelling for him.

During his time in Nuenen Van Gogh’s palette was earth toned, particularly dark brown, and he showed no sign of the vivid colouration that distinguished his later, best known work. (When Vincent complained that Theo was not making enough effort to sell paintings in Paris, Theo replied that they were too dark and not in line with the current style of bright Impressionist paintings.) During his two-year stay in Nuenen, he finished many drawings and watercolours, and nearly 200 oil paintings.

In November 1885 he moved to Antwerp and rented a little room above a paint dealer’s shop in the Rue des Images (Lange Beeldekensstraat). He had little money and ate poorly, preferring to spend what money his brother Theo sent to him on painting materials and models. Bread, coffee, and tobacco were his staple intake. In February 1886 he wrote to Theo saying that he could only remember eating six hot meals since May of the previous year. His teeth became loose and caused him pain. While in Antwerp he applied himself to the study of colour theory and spent time looking at work in museums, particularly the work of Peter Paul Rubens, gaining encouragement to broaden his palette to carmine, cobalt and emerald green. He also bought some Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts in the docklands, which he imitated and incorporated into the background of some of his paintings. It was while living in Antwerp that Vincent began to drink absinthe heavily. He was treated by Dr Cavenaile whose surgery was near the docklands, possibly for syphilis; the treatment of alum irrigations and sitz baths was jotted down by Vincent in one of his notebooks.

In January 1886 he attended Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, studying painting and drawing. Despite disagreements over his rejection of academic teaching, he nevertheless took the higher-level admission exams. For most of February he was ill, run down by overwork and a poor diet (and excessive smoking).

In March 1886 he moved to Paris to study at Fernand Cormon’s studio, and in May 1886 his mother and sister Wil moved to Breda. The brothers first shared Theo’s Rue Laval apartment on Montmartre. In June they took a larger flat at 54 Rue Lepic, further uphill. As there was no longer need to communicate by letter, less is known about Van Gogh in Paris than other periods of his life.

For some months Vincent worked at Cormon’s studio where he frequented the circle of the British-Australian artist John Peter Russell, and met fellow students like Émile Bernard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who used to meet at the paint store run by Julien “Père” Tanguy, which was at that time the only place to view works by Paul Cézanne.

It was not difficult to see and study Impressionist works in Paris at this time. In 1886, for example, two large vanguard exhibitions were staged, the 8th and final exhibition of the Impressionists and an exhibition of the Artistes Indépendants. In these shows Neo-Impressionism made its first appearance; works of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac were the talk of the town. Though Theo, too, kept a stock of Impressionist paintings in his gallery on Boulevard Montmarte, by artists including Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro, Vincent evidently had problems acknowledging these recent ways to see and paint. Conflicts arose, and at the turn of 1886 to 1887 Theo found shared life with Vincent “almost unbearable,” but in spring 1887 they made peace. Then Vincent set out for a campaign in Asnières, where he became personally acquainted with Paul Signac. Vincent and his friend Emile Bernard, who lived with parents in Asnières, adopted elements of the “pointillé” (pointillism) style, where many small dots are applied to the canvas, resulting in an optical blend of hues, when seen from a distance. The theory behind this also stresses the value of complementary colours (for example, blue and orange), which form vibrant contrasts and enhance each other, when juxtaposed.

In November 1887, Theo and Vincent met and befriended Paul Gauguin, just arriving in Paris. Near the end of the year, Vincent arranged an exhibition of paintings by himself, Bernard, Anquetin and (probably) Toulouse-Lautrec in the Restaurant du Chalet, on Montmartre. There, Bernard and Anquetin sold their first painting, and Vincent exchanged work with Gauguin, who soon departed to Pont-Aven. But the discussions of art, artists, and social situations started during this exhibition expanded to visitors to the show like Pissarro and his son, Signac and Seurat. In February 1888, Vincent felt finally worn out by life in Paris. He left the city, completing over 200 paintings in his two years there. Hours before leaving, along with Theo, he paid his first and only visit to Seurat in his atelier.

Van Gogh arrived at the station in Arles February 21, 1888, crossed Place Lamartine, entered the city through the Porte de la Cavalerie, and took quarters a few steps further, at Hôtel-Restaurant Carrel, 30 Rue Cavalerie. He had ideas of founding a Utopian art colony. His companion for two months was Danish artist, Christian Mourier-Petersen. In March, he painted local landscapes, using a gridded “perspective frame.” Three of his pictures were shown at the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. American painter, Dodge MacKnight, who lived in nearby Fontvieille visited van Gogh.

On May 1 he signed a lease for 15 francs a month to rent four rooms on the right side of the “Yellow House” (its outside walls were yellow) at No. 2 Place Lamartine. The house was unfurnished and had been uninhabited a while so he was unable to immediately move in. He had been staying at Hôtel Restaurant Carrel in the Rue de la Cavalerie, just inside the medieval city gate, with the old Roman Arena in view. The rate charged by the hotel was 5 francs a week, which Van Gogh regarded as excessive. He disputed the price, and took the case to the local arbitrator who awarded him a twelve franc reduction on his total bill. On May 7 he moved out of the Hôtel Carrel, and moved into Café de la Gare. He befriended proprietors, Joseph and Marie Ginoux. Although the Yellow House had to be furnished before he could fully move in, Van Gogh used it as a studio. His major project at this time was a series of paintings intended to form the décoration for the Yellow House.

In June van Gogh visited Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. He gave drawing lessons to a Zouave second lieutenant, Paul-Eugène Milliet, who also became a companion. MacKnight introduced him to Eugène Boch, a Belgian painter, who stayed at times in Fontvieille (they exchanged visits in July). Gauguin agreed to join him in Arles. In August he painted sunflowers; Boch visited again. On September 8, upon advice from his friend, the station’s postal supervisor Joseph Roulin, he bought two beds, finally spending the first night in the sparsely furnished Yellow House September 17.

On October 23 Gauguin eventually arrived in Arles, after repeated requests from Van Gogh. During November they painted together. Uncharacteristically, Van Gogh painted some pictures from memory, deferring to Gauguin’s ideas in this. Their first joint outdoor painting exercise was at the picturesque Alyscamps. It was in November that Van Gogh painted The Red Vineyard.

The two artists visited Montpellier in December and viewed works by Courbet and Delacroix in Museé Fabre. Their relationship was deteriorating badly. They quarrelled fiercely about art. Van Gogh felt an growing fear that Gauguin was going to desert him, and what he described as a situation of “excessive tension” reached a crisis point on December 23, 1888, when Van Gogh stalked Gauguin with a razor and then cut off the lower part of his own left ear lobe, which he wrapped in newspaper and gave to a prostitute named Rachel in the local brothel, asking her to “keep this object carefully.” Gauguin left Arles and did not see Van Gogh again. Van Gogh was hospitalised and in a critical state for a few days. He was immediately visited by Theo (whom Gauguin had notified), as well as Madame Ginoux and frequently by Roulin. In January 1889 Van Gogh returned to the “Yellow House”, but spent the following month between hospital and home, suffering from hallucinations and paranoia that he was being poisoned. In March the police closed his house, after a petition by 30 townspeople, who called him fou roux (the redheaded madman). Signac visited him in hospital and Van Gogh was allowed home in his company. In April he moved into rooms owned by Dr. Rey, after floods damaged paintings in his home. On April 17 Theo married Johanna Bonger in Amsterdam.

On May 8, 1889 Van Gogh, accompanied by Reverend Salles, committed himself to the mental hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in a former monastery in Saint Rémy de Provence, less than 20 miles (32 km) from Arles. The monastery was a mile and a half out of town in an area of cornfields, vineyards, and olive trees. The hospital was run by a former naval doctor, Dr. Théophile Peyron, a general practioner. Theo van Gogh arranged for his brother to have two small rooms, one for a studio, although in reality they were simply adjoining cells with barred windows. During van Gogh’s stay there, the clinic and garden became his main subject. At this time some of his work was characterised by swirls, as in one of his best-known paintings, The Starry Night. He took short supervised walks, giving rise to images of cypresses and olive trees, but due to a shortage of subject matter limited access to the outside world, he painted interpretations of Millet’s paintings, as well as his own earlier work. In September 1889 he painted two new versions of Bedroom in Arles, and in February 1890 he painted four portraits of L’Arlésienne (Madame Ginoux), based directly on a charcoal sketch Gauguin had produced when Madame Ginoux sat for both artists early November 1888.

In January 1890, his work was praised by Albert Aurier in Mercure de France, and he was called a genius. In February, invited by Les XX, a society of avant-garde painters in Brussels, he participated in their annual exhibition. When, at the opening dinner, Henry de Groux, a member of Les XX, insulted Van Gogh’s works, Toulouse-Lautrec demanded satisfaction, and Signac declared, he would continue to fight for Van Gogh’s honour, if Lautrec should be surrendered. Later, when Van Gogh’s exhibit was on display with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, Monet called his work the best in the show.

In May 1890, Van Gogh left the clinic and went to physician Dr. Paul Gachet, in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, where he was closer to Theo. Dr. Gachet was recommended by Pissarro, as he had treated several artists and was an amateur artist himself. Van Gogh’s first impression was that Gachet was “sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much.” Later Van Gogh did two portraits of Gachet in oils, as well as a third — his only etching, and in all three emphasis is on Gachet’s melancholic disposition. In his last weeks at Saint-Rémy Van Gogh’s thoughts had been returning to his “memories of the North”, and several of the approximately 70 oils he painted during his 70 days in Auvers-sur-Oise — such as The Church at Auvers — are reminiscent of northern scenes.

Wheat Field with Crows — an example of the unusual double square canvas-size he used in the last weeks of his life — with its turbulent intensity is often, but mistakenly, thought to be Van Gogh’s last work (Jan Hulsker lists seven paintings after it). Daubigny’s Garden is a more likely candidate. There are also seemingly unfinished paintings, such as Thatched Cottages by a Hill.

Van Gogh’s depression deepened, and on July 27, 1890, at the age of 37, he walked into the fields and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. Without realizing that he was fatally wounded he returned to the Ravoux Inn where he died in his bed two days later. Theo hastened to be at his side and reported his last words as “La tristesse durera toujours” (French for “the sadness will last forever”). Vincent was buried at the cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise. Theo had contracted syphilis — though this was not admitted by the family for many years — and not long after Vincent’s death, was himself admitted to hospital. He was not able to come to terms with the grief of his brother’s absence and died six months later on January 25 at Utrecht. In 1914 Theo’s body was exhumed and re-buried beside Vincent.